Why is Zinc essential?

There are more roles for zinc than any other nutrient. It is one of the most important elements for our health, yet one of the most deficient in our diet, especially here in New Zealand.

The chronic lack of zinc in Aotearoa is due to the quality of our soils and the impact of the foods we eat, and the water we drink.

Here’s an overview of the critical roles this mineral plays in our bodies. Also see our handy guide: A to Zinc.

Zinc’s Role

Zinc is involved in hundreds of processes within the body, and it helps us absorb and utilise nutrients from our food.

It plays a role in immune function, helping repel and overcome bacterial and viral infections like the common cold. It assists with growth development, protein and DNA synthesis, and is effective in wound healing.

Zinc is essential for the brain and neurological function as well as the maintenance of vision, taste and smell. It nourishes the scalp and helps maintain strong and healthy gums, hair, skin and nails. It can help avoid hair loss, which can be a symptom that you may be deficient. Zinc can control the production of oil in the skin and help balance some of the hormones that can lead to acne. Many skin disorders can be attributed to insufficient zinc.

Zinc is important to our health and wellbeing throughout our life. It supports normal growth and physical development during pregnancy, and this support continues through childhood and adolescence.

There is almost no part of the body that zinc doesn’t benefit, either inside or out.

It is key to both male and female reproductive health and is vital as we grow older, as it helps maintain bone density and muscle bulk.

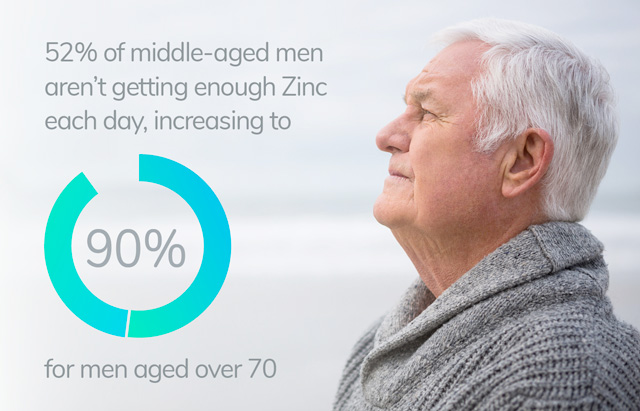

However, zinc can be harder to access through diet for both women and men as they age, as the body doesn’t have the ability to store minerals. New Zealand surveys have shown that 52% of middle-aged men aren’t getting enough zinc each day, and that figure increased to 90% for men aged over 70.

Zinc and the Common Cold

Much research has been done around zinc and its capacity to combat the common cold. Although studies examining zinc treatment on cold symptoms have shown varied results over years, it appears to be beneficial under certain circumstances.

The Cochrane Report concluded that taking it within 24 hours of developing symptoms has been shown to reduce the severity and duration of cold symptoms in healthy people by up to a third. It does this by directly inhibiting the rhinovirus binding and replicating and suppressing inflammation.

More research is needed to determine the optimal dosage, formulation and duration of treatment before a recommendation for zinc in the treatment of the common cold can be made.

Some of us need zinc more than others.

Studies have shown that New Zealand men have lowered zinc status, especially as they age. Men require an RDI of 14mg just to prevent deficiency.

Several New Zealand studies have suggested that many adolescent girls aren’t getting enough zinc and this may be affecting their growth and development. This could be due to changing diets, less red meat and seafood being consumed, as well as the prevalence of processed foods, which are often refined and lacking minerals and other nutrients.

Pregnant and breastfeeding mothers also require bigger intakes, as there are high foetal requirements for zinc, and lactation can also rapidly deplete mineral stores. Breast milk provides enough zinc (RDI 2mg) for baby for the first six months, but zinc needs to be acquired from food sources as the child grows. Supplementation of zinc has been shown to improve the growth and development of some children who have exhibited a mineral deficiency.

Zinc has limited storage capacity with our body, so a deficiency can develop quickly if we’re not restoring and replenishing.

Diagnosing Deficiency

Blood tests are not a reliable method for detecting zinc deficiency as most of the zinc in our bodies is retained in our cells rather than in our blood. However, there is a simple test you can take to measure your zinc status, which can often be provided by your local health shop.

It involves taking a tiny amount of zinc sulphate, dissolving it in water and then tasting as little as a spoonful. This test works because zinc is required for your taste buds to function.

If you notice a bitter, astringent taste you are not deficient. If this bitter taste is delayed by more than a few seconds, you need more zinc in your diet. If there is a much longer delay or if you don’t notice the bitterness or it tastes like water, you may have a deficiency and will need to restore your zinc levels.

In this case, you may already be experiencing some common symptoms of a low zinc status such as frequent colds or infections, weak sense of smell and taste, hair loss, slow wound healing or skin disorders and inflammation.

You may be advised to supplement with zinc for a period and look to include more zinc-rich foods in your diet, such as lean red meat, dairy, seafood, poultry, or whole-grains, beans and legumes.

Getting Zinc into Your Daily Diet

The best source of zinc is rock oysters, which contain significantly more zinc than red meat and grains but are often not a regular part of our diet. Fats, which contain very little zinc, also tend to dilute zinc from the diet.

Lean red meat is an excellent dietary source, and it is also highly bioavailable, meaning your body can absorb it much more readily. Green leafy vegetables and fruits contain modest sources of zinc.

Some animal-free options include whole-grain breads, cereals, nuts, seeds, beans and legumes, but these foods also contain phytates, which can bind zinc and therefore inhibit its absorption. While these plant-based options are good dietary sources, the bioavailability is often lower than animal- based products.

Vegetarians often require as much as 50% more of the RDI for zinc than non-vegetarians.

Note that techniques such as soaking beans and grains in water for several hours can reduce this binding of zinc by phytates and thus increase bioavailability. Vegetarians often require as much as 50% more of the RDI for zinc than non-vegetarians.

Studies from New Zealand nutrition surveys and overseas research suggest most of us are accessing only half of the daily zinc we require from our diet.

Zinc Deficiency Inhibits Absorption

Once you become zinc deficient, it can be very difficult to improve zinc levels purely through food alone, as your body’s absorption often depends on having enough zinc in the first place.

In addition, if you are recovering from an operation, have suffered emotional stress, or been over-exercising, your body will look to use all the available zinc on offer in an effort to heal. Zinc is one the few minerals lost rapidly in the urine after suffering acute psychological stress.

Gastrointestinal surgery and digestive disorders such as Crohn’s disease can decrease zinc absorption. Other illnesses associated with zinc deficiency include chronic liver disease, alcoholic cirrhosis, anorexia nervosa, chronic renal disease, diabetes, malignancy and sickle cell disease. Diarrhoea can also lead to excessive loss.

Supplementation may then be required to achieve good zinc status and you will then be able to maximise your zinc from food sources once again.

-

Zinc Liquid Mineral$27.90

Zinc Liquid Mineral$27.90

Summary

While we should be getting our important vitamins, minerals and other nutrients from the food we eat, there are often factors that prevent this from happening.

Soil depletion, the prevalence of processed food and bouts of illness can lead to mineral deficiencies that prevent the nutrients reaching the cells in our body and enabling the hundreds of processes that keep us healthy.

It is important to be aware of some simple things we can do to restore and replenish these minerals, to maintain optimal levels and supplement when needed to avoid larger health problems.

References:

Coory, David. Stay Healthy by supplying what’s lacking in your diet. 1992

Schauss, Alexander G. Minerals, Trace Elements, & Human Health. Life Sciences Press. 1995

Institute of Medicine, Food and Nutrition Board. Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin A, Vitamin K, Arsenic, Boron, Chromium, Copper,

Iodine, Iron, Manganese, Molybdenum, Nickel, Silicon, Vanadium, and Zinc. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 2001

Singh M, Das RR. Zinc for the common cold. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011

Prasad AS. Zinc deficiency: its characterization and treatment. Met Ions Biol Syst 2004

Disclaimer:

The information in this article is not intended as a medical prescription for any disease or illness. Nothing stated here should be considered medical advice. Use as directed. If symptoms persist, consult your healthcare professional.